March was filled with nature for me. In early March, I again attended the Michigan Wildflower Association Conference in East Lansing. It’s always interesting and inspiring. This year, I enjoyed a presentation by Shelley Stusick of a grassroots program called “Go Beyond Beauty.” Its goal is to celebrate businesses and ordinary citizens who “make decisions that benefit their local habitat” and to educate about managing invasive species and promoting “native replacements for common invasive ornamental plants.” Great name, great speaker, great goals!

I also attended an excellent Q & A panel discussion called “How to Do a Native Garden,” which included three knowledgeable people from a native plant nursery, a native seed farm and a native landscape design business. All of this helped me create a presentation for a local garden club on including native plants in our home landscapes.

Now I am definitely NOT an experienced native gardener; I’ve only been restoring my yard for the last 5 years. But for nine years, I’ve learned about native plants from our Natural Areas Stewardship Manager, Dr. Ben VanderWeide, who has multiple native gardens around his home. And I have friends with beautiful, lush native gardens and much more experience with native gardening than I.

So inspired by “Go Beyond Beauty,” I’ll endeavor here to share a taste of what they’ve shared and what I’m learning about native gardening in general. And then I’ll provide my idiosyncratic “catalog” of favorite native plants that you might want to consider for your yard and garden.

Native Plants Provide Beauty … and Nourish Our Wild Neighbors

First, I want to establish right away that “going beyond beauty” does NOT mean no beauty! Native plants are very beautiful.

But what’s “beyond” beauty is the value of restoring health to the habitat around you. As counter-intuitive as it may seem to many gardeners, if caterpillars are missing in your gardens, the habitat around you may be a lovely, green desert! Does that sound extreme? Let me briefly explain.

The goal of gardening with native plants is to create beautiful gardens that provide nature’s most essential food – the native leaves that our native caterpillars can eat. Weird, eh? Bees of course pollinate – and not just non-native European Honeybees. Michigan’s 465 species of native bees have been pollinating here for thousands of years!

But caterpillars grow up to be the adult pollinators that fly and flutter over our flower beds and fields. Butterflies take the day shift; moths hold down the night shift. And smaller pollinators live unnoticed all around us. The adults of these creatures eat by sipping nectar or collecting pollen from almost any flower. But their young, the caterpillars, only eat leaves. And it turns out, the vast majority of their young can only eat the leaves of a few native plants!

(Solidago speciosa.)

The reason? All plants produce chemicals, some just distasteful, some toxic, to ward off predators. Over millennia, caterpillars only learned to tolerate a few of those toxins. The Monarch caterpillar (Danaus plexippus), a well-known example, adapted to eat exactly one group of plants, milkweeds. But it isn’t alone in being a specialist. If the caterpillars of most native Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) eat the leaves of non-native plants in your garden or mine, they either find the leaves unpalatable and starve, are too deformed to reach maturity, or are poisoned and die from an unfamiliar toxin. And when caterpillar numbers decline, obviously so do the numbers of adult pollinators – and the many other creatures in any habitat that depend on them!

Caterpillars are the essential food source for both our baby birds and their adults, as well as spring and fall migrators, frogs, turtles, and mammals large and small farther out in the food web. Caterpillars are filled with the protein and fat that wildlife relies on year ’round. So in every habitat, nature’s most essential food source is the leaves of native plants that feed the the most numerous leaf-eaters in the world, i.e. caterpillars.

by Paul Birtwhistle

Photo by Paul Birtwhistle

Photo by Paul Birtwhistle

So, yes, that means some chewed leaves or missing buds. But that’s a small price to pay for feeding baby butterflies and baby birds and all the other creatures around us that depend on caterpillars. That’s a big part of what’s meant by “going beyond beauty.”

For a more thorough discussion of “why native plants,” have a look at the blog I wrote in 2019 when I took my first steps toward native gardening at our home.

Planting Native Around Your Home

If you’re at this point in the blog, you know the rationale for the importance of native plants. So here are some native gardening tips to get you started.

Be Sure You’re Planting Native Plants!

“Nativars” are native plants that have been cultivated for a specific trait – double blossoms, a different color, pattern, or scent. Many nativars are sterile and don’t produce pollen for the bees. Some don’t even produce nectar for adult butterflies. The butterfly or other pollinator of that plant might pass right by their preferred flower without recognizing it if the shape, color or scent are even slightly altered.

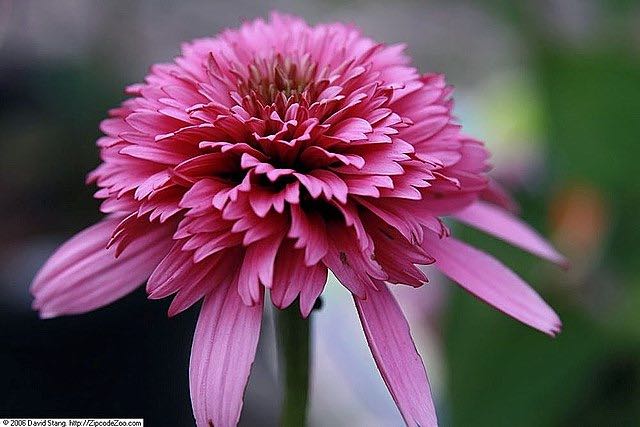

Here’s a native Purple Coneflower on the left and a nativar on the right, appropriately named “Razzmatazz.” Such double blossoms may be sterile, according to entomologist and Professor Douglas Tallamy, author of Bringing Nature Home, an engaging, easy-to-read book on the importance of native gardening. When so much of the plant’s energy goes into producing a jazzy blossom, there’s not much left for making pollen or nectar.

with Monarch Butterly

Nativars are often identified with the native flower’s scientific genus name or both the genus and species names, with a catchy name after that, like this coneflower, Echinacea pupurea, ‘Razzamatazz.’ Scientific names of native plants are easily found online by just putting in the common name. I’ve given you both below for the plants I’m covering.

Sourcing Native Plants

Michigan native plant nurseries and local native plant groups hold sales events for native gardeners in the spring and fall. Check out this great list of native plant sales in southeast Michigan from North Oakland Wild Ones! Some native plant nurseries have limited hours for retail sales, because they supply wholesale more than retail. Local garden clubs and other grass roots organizations that promote pollinator gardens have experienced gardeners and also offer local native plant sales – some of which have already started this May’s pre-sale ordering. And if you are lucky enough to know native gardeners, they may generously share some seeds or seedlings with you. Needless to say, collecting plants and seeds in parks or on private land without permission is not an option!

DISCLAIMER: Oakland Township Parks & Recreation does not endorse or promote any business entity which produces or markets native plants or seeds, or which provides landscape design or installation services. This discussion is provided for informational purposes only.

Dream Big, but Start Small

Please know that my gardening friends and I are NOT advocating that you immediately tear up your gardens and start over (though if you know what you’re doing, go for it!) But perhaps try adding a few native flowers each year in your current beds. Or add some native trees or shrubs to your yard. You might actually want to reduce your non-native lawn which requires regular fertilizing, mowing and watering and replace some of it with a small native bed that doesn’t need as much tending. And then let it expand over time, leaving the turf grass for play areas or paths between beds.

Maintaining Native Plants

Once established, native plants are incredibly hardy. They don’t usually need watering unless we’re in a long drought, or if you planted them in a dry place when they prefer moisture. Many native plants are used to growing in poor soil, so fertilizing in a native bed is not necessary or even recommended.

If you’re adding native plants to a bed that you’ve fertilized for your non-native plants, some natives may be too vigorous. In highly fertile soil, they can grow leggy or become aggressive, needing to be thinned or moved to an unfertilized bed. Start small if you’re new to native gardening. Then watch, be curious, learn how your native plants actually grow – or don’t – in your light and soil. Be willing to move some to a new location or just eliminate them.

Don’t panic and give up on a native plant if it gets skeletonized by insects or buried under piles of dirt or run over by a sloppy contractor – all things that have happened to me! Native plants grow deep roots; some don’t fully bloom for 3 years while roots develop. And they come back time after time to try again, like the the Poke Milkweed (Asclepias exaltata) below with its delightful “fireworks” effect.

If you are creating a new bed in a grassy area, be sure to get rid of the grass thoroughly before starting a native planting. I didn’t with some of my beds and have lived to regret it! For a small new garden bed you can get the space ready by laying down a layer of cardboard, topped by a thick layer of mulch for a growing season before putting in plants.

Designing with Native Plants

Native plants generally look best when planted in groups, massing colors, rather than one plant here, one there. So you might want to buy multiples of the same species and create drifts of color.

However, some are so glamorous that you’d love to use them as specimen plants, the Swamp Rose Mallow (Hibiscus moscheutos)or Michigan Lily (Lilium michiganense) fit the bill nicely.

If you want your garden to be more understandable to neighbors, you can mulch between the drifts, which makes the garden easier to weed and has a more formal look. For a more natural look, plant ground covers rather than using mulch between the groups. One landscape designer suggested planting one group inside another and a gardener friend of mine does that successfully.

The designer also suggested planting aggressive native ground covers, like native Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), only after your other plants are established or it could might get rambunctious and take over the whole area! Wild Ginger (Asarum canadense) is less aggressive and has a lovely red flower hidden under the leaves! When the flowers finish on these plants, the leaves remain.

One gardener friend recommended being willing to follow nature. Some plants may jump to more advantageous areas, or spread beyond your original plan. Be patient and curious and know that your garden may change a bit year to year. Native plants are not as predictable as cultivated non-natives – but that’s part of the fun of it. Just see what nature is showing you and try to be adaptable. You can always thin or eliminate something that isn’t working, just as you would with non-native plants. Gardens like this local one in Oakland Township are an ongoing adventure in learning about nature.

Planting Native Plugs or Seed

Installing live plants, often sold as “plugs,” will give you more control over where each type of plant will grow, and help plants establish more quickly. Plugs make the most sense for formal garden beds and for smaller spaces. Compared to seed, plugs are more expensive, take more time to install, and need watering for the first growing season. Native plant seed mixes are often less expensive for larger areas, take less time to install, and generally don’t need to be irrigated, but you will have less control over where each species grows. Design your seed mix to match your soils and amount of sun or shade, and let the plants sort it out after that!

Michigan has nurseries that grow Michigan native plants for seed. Generic “prairie” or other “wildflower” mixtures found online or in big box stores sometimes contain seed that won’t succeed, or may become invasive, in Michigan conditions. My elder sister purchased a wildflower mix for the slope behind her new house. She got a big, beautiful bloom the first year but never saw most of those plants again. Even native plants will come and go in a meadow because of competition and weather events. But planted in the right location, they predictably thrive.

Ideally, you want species adapted to Michigan’s soil and climate, so look for seed or plants from “Michigan genotypes” when possible. Native seed should be sown in late fall or even winter. The cold actually helps the seeds germinate. Many native seeds need only be tossed on the ground or covered with just a thin layer of soil, if any. After all, they’ve been seeding that way for thousands of years! Rain, snow and frost will drive them down into the ground as necessary.

Enough with the Preliminaries! Let’s Talk Plants!

OK! Remember, though, that this is just some “greatest hits,” a place to begin with native gardening. Explore the websites of native plant and seed providers and visit with other native gardeners for more ideas.

SPRING FLOWERS AND SHRUBS

DRY, SUNNY SPOTS

FOR DRY SHADE

SUN AND AVERAGE TO WET SOIL

Eye-popping yellow.

SPRING-BLOOMING SHRUBS AND TREES

Photo by Dan Mullen, (CC BY-NC-ND) on Wikimedia

Photo by Tom Scavo CC BY at iNaturalist

Need a male and female. Early blooms with lots of pollen and nectar, so pollinators love them.

SUMMER FLOWERS AND SHRUBS

FOR DRY SUN

FOR A SUNNY, MOIST SPOT

SUMMER-BLOOMING SHRUBS

Our summer-blooming shrubs produce fall berries that feed local and migrating birds! According to research in an Audubon Society report, berries of our native shrubs have more nutrition than fruits of non-native shrubs, which provide mostly sugars – the fast food of the plant world, perhaps? So migrating birds, for example, prefer their familiar native berries and tend to seek out non-native berries only when native berries are gone for the season.

RED OSIER/RED TWIG DOGWOOD (Cornus sericea) needs room to spread, but its flowers, its nutritious berries and its bright red winter stalks offer changing color for the whole growing season. A gardening friend succeeds in keeping it in her garden by tightly surrounding it with other plants.

Photo by Laval University, CC BY-SA, 4.0, via Wikimedia commons

PURPLE/BLACK CHOKEBERRY shrubs (Aronia prunifolia) (as distinguished from Chokecherry trees) may be a naturally occurring hybrid between 2 native shrub species. So you may see the common name as Purple Chokeberry. The berries aren’t edible for us (except maybe in jams), but birds love them. Chokeberry isn’t a spreader, though with all those berries, it’s probably better to keep it away from walkways or plant it at the edge of a yard.

AUTUMN FLOWERS AND SHRUBS

Autumn plants supply late season pollinators with just what they need – nectar and pollen. The asters and goldenrods are the stars of the season. (And no, goldenrods don’t make you sneeze because their pollen’s too heavy to be carried by the wind. The sneeze culprits are yellow Ragweeds (genus Ambrosia) that bloom at the same time!)

FOR SUNNY DRY SPOTS

FOR SUNNY AND MOIST GARDENS

Likes moisture. May need support in fertilized soil.Gorgeous with goldenrods

A misnamed plant; no sneezing! Flowerheads can be ball-shaped or flat. Likes moisture.

OTHER LATE SUMMER/FALL PLANTS TO CONSIDER

Light blue flowers and graceful stems.

A STANDOUT FALL SHRUB WITH RED, NUTRITIOUS BERRIES THAT BIRDS LOVE!

Michigan Holly/Winterberry (Ilex verticillata) is a larger shrub for sun to partial shade, growing from 6 to 12 feet high. It prefers moist areas and acid soil, but can get along in average soil, where it is less likely to spread than in moist soil. Like all holly bushes, you need a male and female so it can be pollinated and form berries. (Be aware that this shrub has a lot of cultivars and nativars! We want the nutritious native berries to feed the birds.) It blooms in July and what beautiful, red berries come from those flowers! In the fall, the leaves drop and the berries remain…at least until the birds spot them!

REMEMBER TREES: THE BEST HOST PLANTS!

If you have room in your yard, consider planting a tree or two! Some of them host hundreds of pollinator young high in their canopy, under their bark, or within fallen leaves – where you’ll never notice them. Here’s the top three from Professor Doug Tallamy’s list of “Best Bets” for our area: Oaks (g. Quercus) hosts 454 species of pollinator caterpillars; Willows (g. Salix) – sadly not the non-native Weeping one – host 430 pollinator species and Cherries (g. Prunus) comes in third with hosting 413 pollinator young. But more about them in a future blog!

From a Stage Set to a Living Community

I’ll be the first to admit that I never really gave much thought to my gardens and yard as “habitat.” I always thought of flowers as decorating or beautifying the house and yard. Until I began to learn about the crucial role of native plants in feeding and sheltering nature, I also experienced fields and forests as landscapes – green, colorful or snow-covered – as backdrops on the stage of my life. Now I’m beginning to appreciate that I’m simply a cast member on that stage. And I’m enjoying getting to know my fellow players.

I’ve learned, for instance, that some male bees, unwelcome in the hives or holes of females, often sleep in flowers!

And I discovered that the colorful dragonflies whirring across a meadow have spent months or even years developing underwater in a nearby wetland.

I came to respect Turkey Vultures (Cathartes aura) who clean up so thoroughly that I rarely see a carcass in any of our parks.

Last summer, I noticed with a laugh the tiny native Digger Bee (genus Anthophora), proboscis at the ready, sampling flowers in the small, native meadow we planted when a windstorm flattened part of our woods.

Shakespeare observed in his comedy, As You Like It, “All the world’s a stage.” But now I know that it isn’t just “all the men and women” who are “players” on that stage. All around us is a community of living beings who each play their part in the landscape. By tending native gardens and stewarding productive, healthy habitat around us, we get more than just beauty. We find ourselves surrounded by fluttering, buzzing, scurrying, singing life itself! And we discover ourselves as members embedded in a natural community that needs us to play our part in its restoration after years of unwitting neglect. Doing so to the best of my ability has been deeply good for me, a way to make a difference in a challenging time. Maybe give it a try? Go a step or two “beyond beauty” this summer and see what you discover.